Inspired by Mozart’s Piano

The Harvard professor Robert Levin is considered to be one of the most important Mozart

researchers of our time. Now he has recorded Mozart’s piano sonatas on the composer’s own instrument. Mario-Felix Vogt from the German/Dutch magazine PIANIST spoke with him about ornamentation, knee pedals and the influence of C.P.E. Bach.

Many pianists have tried their hand at Mozart’s piano sonatas, with the most varied approaches. Murray Perahia strove for a noble, beautiful sound in these pieces. Friedrich Gulda focused on the motoric aspects, while Vladimir Horowitz treated them like Romantic works. But it would be hard to find a pianist who has recorded the works on the basis of such profound historical knowledge as Robert Levin. Born in New York City in 1947, this pianist and musicologist is considered one of the most important Mozart researchers of our time. He studied composition under Stefan Wolpe and Nadja Boulanger, attended masterclasses by pianists such as Clifford Curzon and Robert Casadesus, and studied musicology at Harvard University, where he already developed a keen interest in Mozart’s music; his dissertation entitled The Unfinished Works of W.A. Mozart reflects this. After graduating in 1968, he was appointed head of the music theory department at the renowned Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia on the recommendation of the pianist Rudolf Serkin. In the 1980s Levin was a piano professor at the Hochschule für Musik Freiburg, and in 1993 he became a professor of musicology at Harvard University.

Completion of the Requiem

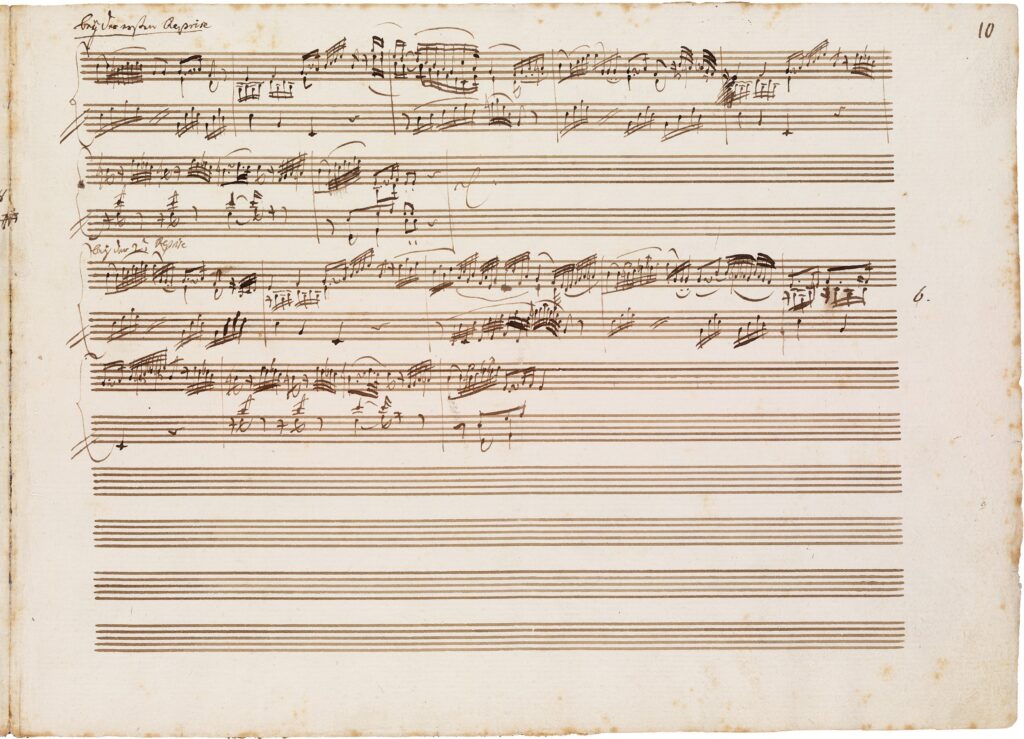

Levin has performed as a pianist since his youth. His first Mozart recordings were made in 1986, when he recorded concertos for three pianos with his fellow pianists Malcolm Bilson and Melvyn Tan. He also recorded a whole series of Mozart piano concertos in the 1990s, under the baton of the English conductor Christopher Hogwood. As a musicologist, Robert Levin has been very influential in creating a new image of Mozart. His intensive study of the compositions of the composer from Salzburg has led to several reconstructions of his works, such as the Sinfonia Concertante, K. 297b, for four wind instruments and orchestra. Above all, however, his completion of the Requiem earned him great recognition, both in scholarly circles and among musicians. In 1991, Levin’s version of the Requiem was premiered to great acclaim under the direction of Helmuth Rilling; several recordings of it have been made, and the score has also been published. Now the American pianist has recorded all 18 piano sonatas, including three fragments he has completed himself. What is special about this recording is not only that it is based on the latest philological and performance research, but also that it was made on Mozart’s own instrument.

‘Mozart’s fortepiano was probably built by Anton Gabriel Walter around 1782’, Levin explains. ‘He composed and played on this instrument in his mature Viennese years. He performed all his great piano concertos, solo works and chamber works with piano on it.’

Soundboard untouched

According to Levin, the instrument was reconditioned after Mozart’s death before it was sent to his son Carl Thomas in Milan. A further refurbishment took place in the 1930s. Surprisingly, apart from

the usual consumables such as individual strings and the leather covering of the hammer heads (hammer heads made of felt were a later development), no major parts of the instrument had to be replaced. ‘The body is original, even the soundboard is untouched’, Levin emphasises. Compared to a grand piano of today, Mozart’s instrument sounds significantly different, Levin continues: ‘The strings were thinner back then, the notes decay faster, and the instrument speaks more than it sings.’

Until now, the piano has only ever been made available for individual performances, and not for such an extensive project as recording 18 piano sonatas. ‘This complete recording is unique, says Levin, confessing that he really ‘got goose bumps’ when he imagined that Mozart had played his piano concertos to an enthusiastic audience on this very instrument. Unlike modern pianos, he says, his instrument does not require any special effort to bring out the melody over the accompaniment. ‘On a piano from Mozart’s time, where the strings are not cross-strung as they are today, but are parallel, everything automatically sounds well balanced in terms of dynamics."

Knee levers as precursors of the pedals

The pedals in Mozart’s time, too, were designed differently from today. For example, pianos in the late 18th century usually had hand levers with which the player could raise the dampers from the strings. In addition, many instruments had a moderator slide: ‘When you pull the button, a layer of felt is inserted between the hammer heads and the strings, producing a wonderfully soft and delicate sound.’ On Mozart’s Walter piano, however, the hand levers for disengaging the damping were probably later replaced by knee levers. ‘It then had a left and a right knee lever, which was rather unusual at the time’, Levin explains. ‘One lever lifted all the dampers, the other lifted only the dampers in the treble. That gave you the flexibility to let the underlying notes “speak” without things getting too muddy in terms of sonority.’ For his recordings of the Mozart sonatas, Levin also used the knee levers, but only ‘very sparingly’, because ‘in the 18th century, the use of the pedal was rather the exception, to achieve a special effect.’

Levin places particular emphasis in his recording on the numerous non-notated ornaments that he adds in the repeats. ‘These correspond to the convention of Mozart’s time’, he explains. ‘And we have proof of this, for instance, in the Sonatas with Varied Reprises by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. He explicitly composed these sonatas because he says the modification of the reprises is acknowledged by everyone and is common practice. And for those who didn’t possess the inventiveness themselves, he wrote out ready-made solutions.’ ‘It is impossible to overestimate the importance of C.P.E. Bach for the next generation. Mozart wrote about him: “he is the father, we are the sons”. The Sonatas with Varied Reprises were part of the Mozart family’s music library’, Levin continues. ‘So it is not just a hypothesis. There is even a letter from Mozart’s father Leopold to Immanuel Breitkopf of the music publisher Breitkopf & Härtel, where he refers to C.P.E. Bach’s Sonatas with Varied Reprises and says that these sonatas were very successful and that his son could also compose such works. So it was one hundred percent clear that this way of making music corresponded exactly with the artistic customs of the time. And I am very grateful to have received the commission to edit these C.P.E. Bach sonatas before making the Mozart recordings. I was therefore able to take this knowledge into account when recording the Mozart sonatas.’

Text by Mario-Felix Vogt

This article is a contribution from the German and Dutch magazine Pianist through Piano Street’s International Media Exchange Initiative and the Cremona Media Lounge.

Pianist Magazine is published in seven countries, in two different editions: in German (for Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxemburg and Liechtenstein) and in Dutch (for Holland and Belgium).

Pianist Magazine is published in seven countries, in two different editions: in German (for Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxemburg and Liechtenstein) and in Dutch (for Holland and Belgium).

The magazine is for the amateur and professional alike, and offers a wide range of topics connected to the piano, with interviews, articles on piano manufacturers, music, technique, competitions, sheetmusic, cd’s, books, news on festivals, competitions, etc.

For a preview please check: pianist-magazin.de or www.pianistmagazine.nl

Comments