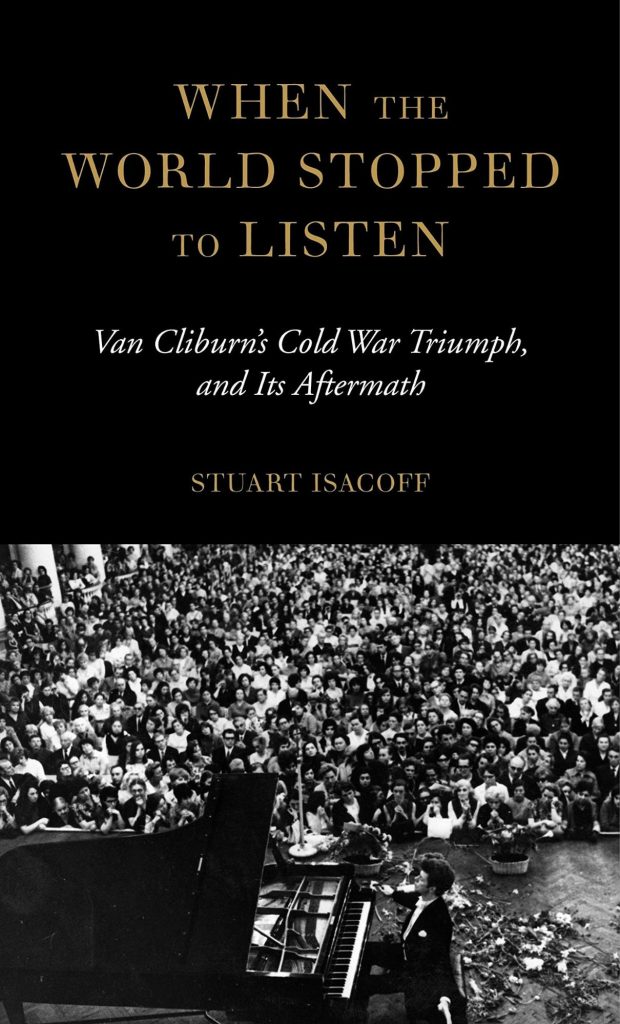

Success, or Just a Sensation? Stuart Isacoff on Van Cliburn’s Moscow Win — 60 Years On

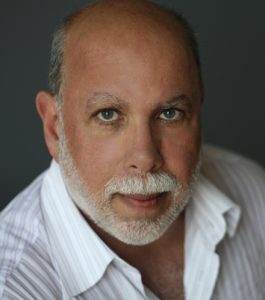

When Stuart Isacoff received an assignment to write a cover story on Van Cliburn’s comeback to the concert scene, this led to a friendship between the two that lasted until the pianist’s death.

Piano Street’s David Wärn has met the author of When the World Stopped to Listen: Van Cliburn’s Cold War Triumph and Its Aftermath, a personal and moving book presenting a sympathetic but honest account of the life of the legendary American pianist.

When Van Cliburn died on February 27 in 2013, the whole world was reminded of his sensational 1958 win at the inaugural Tchaikovsky competition in Moscow. Since then, two important biographies of Cliburn have been written. For the British historian Nigel Cliff, whose Moscow Nights: The Van Cliburn Story was published just before Stuart Isacoff’s book, Cliburn’s death and the ensuing obituaries provided the first opportunity to hear the full story of the pianist’s life, a tale that he thinks resonates particularly strongly today: “while we contemplate talk of a new Cold War, it can be illuminating to recall that Russia and America have had a love-hate relationship for a long while.” Isacoff, on the other hand, had wanted to write Cliburn’s biography since the late 1980s — his basement was already full of material for the book, including taped interviews with Cliburn’s boyhood friends and relatives. Isacoff, with his stronger personal connection to the subject matter and his background as a pianist, unsurprisingly provides a more knowing and intimate portrait. He also a tells a more coherent tale, taking in the larger picture without losing focus on the main character and on the cultural, political and artistic significance of Cliburn’s life story. However, for those interested in as many details as possible about the political processes of the Cold War, Cliff’s book might be a good complement.

‘The Rise and Fall and Rise of Van Cliburn’

In 1989, Van Cliburn returned to the concert scene after an eleven-year break. Isacoff received an assignment from a magazine called Ovation to do a cover story on Cliburn and his comeback. The magazine no longer exists; in fact it went under with that cover story, and Isacoff was never paid. “Van said it probably went under because his picture was on the cover. I said no, it was because of my writing.”

The editor wanted a negative story. He showed Isacoff a photo of Cliburn and said ‘look at that smug smile on his face’. Isacoff didn’t think it looked smug at all, but soon realized that Cliburn was looked down on by some people. “Van was considered sort of phony. You take a New York intellectual snob looking at him, and… he was just perceived as being a country bumpkin. He was very flamboyant, and sentimental — not an urban personality.”

Isacoff started to do research, listening to Cliburn’s recordings. “I thought, this is so beautiful… I can’t write a negative story about this man. I didn’t have it in my heart to do that. So I ignored that part of it. I flew to Fort Worth, Texas, and met with him there; it was one of the years when they were having the competition. He didn’t like to give interviews, and wouldn’t let me take him somewhere to talk privately. Instead, he stood in the middle of this room with people running over and hugging him, exclaiming: Van, Van…! He was taking time to individually hug each person and look in their eyes. He said: go ahead, interview me while I’m doing this. So I spoke with him and took notes while he stood there hugging people.” Isacoff called his article The Rise and Fall and Rise of Van Cliburn. “Van was really happy with it. His mother said there was never any fall, so she didn’t like that part.”

An utterly Van-like evening

In september that year, Cliburn performed the Tchaikovsky concerto at the opening of the Meyerson Concert Hall in Dallas. On the basis of his article, Isacoff was invited to Cliburn’s private dinner party afterwards, and was entranced. He decided that he was going to write a book about the pianist. Not only did Cliburn play like an angel: the history of what he had done, his relations with Kruschev and the Soviet people — Isacoff found all this extremely fascinating.

He went to Cliburn’s boyhood town of Kilgore, Texas, to interview the pianist’s old neighbors and boyhood friends. Cliburn also came to do a recital, in order to raise money for the Harvey Lavan and Rildia Bee Cliburn Scholarship. In his book, Isacoff writes about that “beautiful, strange, and utterly Van-like evening”: Cliburn always had terrible stage fright, and it was much worse in front of neighbors, friends, and family. His hands were shaking so badly that after barely making it through the first piece he left the stage. After about twenty or thirty minutes, he reappeared and continued, suddenly cool and calm. Later in the evening, a weight seemed to have lifted from his shoulders. There was a little buffet in the gymnasium at Kilgore College, and Van was going around inviting people to go to the town church — this was around midnight — where he had convinced the organist to open up the church and give an organ recital in the middle of the night.

Stuart Isacoff

Isacoff had done several interviews with people in Kilgore and New York who knew Cliburn and went to school with him, when he found out that Cliburn really didn’t want him to write the book. “I had all these little tape cassettes, which I stored in my basement. I put it all away when I heard he didn’t want me to do it. Then, more recently, it seemed like it was time to take it all out again and start writing. All these years later, these tape cassettes still work, which amazed me.”

The American Sputnik

Van Cliburn was taught by his mother, Rildia Bee, herself an accomplished pianist who had studied with Arthur Friedheim, a pupil of Liszt. He began giving recitals at four and made his orchestral debut at twelve, in Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto with the Houston Symphony Orchestra. At the Juilliard School of Music in New York, he studied with Rosina Lhévinne, and after winning the prestigious Leventritt award he embarked on a series of debuts with major American orchestras. But with his win in Moscow, the tall, 23-year-old Texan, powerful in performance yet radiating a kind of childlike innocence, became not only a successful pianist, but a symbol for American greatness.

The American victory came as a stunning surprise. The Tchaikovsky Competition had been conceived by the Soviet regime as a showcase for Russian artistic supremacy, illustrating what the poet Mayakovsky had described as the opposition between “the materially poor but spiritually dynamic Soviet Union and the rich but spiritually poor United States.” Tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union had been steadily rising since the launch in 1957 of the first Sputnik space satellite. But while his Russian rivals at the competition were extremely well trained, their performances paled compared to Cliburn’s heartfelt spontaneity and his enormous, singing sound. There was something different about Van’s art; also, it was obvious that he had a deep, genuine love for Russian music. Observers in both the Soviet Union and the United States began to refer to Van Cliburn as ‘the American Sputnik.’

According to Isacoff, this was a role he never wished for. “He didn’t care about politics at all. He was made an icon in the West because of the Cold War, and because of the fact that the US was behind in the space race. When he won, he was presented in the media as the American who conquered the Soviets. But he never saw it that way. He loved people; he just wanted to… spread the love. That’s partly why the Soviet people fell so in love with him. In fact, his friends in New York used to laugh at him because he was overly sentimental, gushing all the time. Everything was love… they were too sophisticated for that. He was perceived as being not real, while in fact he had no pretenses at all. But the Soviets ate it up, and returned those warm feelings to him. He was treated so beautifully there that he wanted to go back over and over again.”

Van Cliburn celebrates with Emil Gilels

‘Oh no, I’m not a success, I’m just a sensation’

When Cliburn returned from the competition, several reporters flocked to New York’s Idlewild Airport to meet him. You must think you are a big success, one of them threw out. Oh no, I’m not a success, I’m just a sensation, answered the young prize winner. He was received by a ticker-tape parade in New York, and soon made a million-selling recording of the Tchaikovsky concerto, but after some time critical misgivings began to be voiced. Everyone had expected his qualities to mature and deepen, but this never seemed to happen. Cliburn found the treadmill of a concert career less and less bearable, and his words at the airport tragically rang more true as his career went on. “He was not psychologically prepared for what happened, and burned out very quickly. It was overwhelming. He was not used to having to perform all the time, and they always wanted the same pieces: Tchaikovsky 1st and Rachmaninoff 3rd. He became almost like a robot,” says Isacoff.

“People like Kirill Kondrashin, the conductor, said to him: Van, you have to take time off. You need to relax and study, to deepen your understanding and not wear yourself out. But Van said: Kirill, I can’t stop, because if I do people will forget me. A lot of that probably came from his mother, who became his road manager and kept him in line. She was very strict — not an easy person, and not particularly nice. But he was devoted to her; she lived almost to a hundred, and he took care of her. But the psychological impact of that was not good.”

Other types of problems also rose in Cliburn’s life. “He was getting injections for a while from a doctor, Max Jacobson, who was nicknamed Dr. Feelgood. He administered amphetamines and other medications to famous artists, movie stars and politicians, including John F Kennedy. And Van got hooked on that. When that was over, he found other obsessions, like astrology. He was afraid to go on stage unless the stars said it was a good day to do it. He was always nervous, and had terrible stage fright. Recording was very difficult, because he pictured that students from Juilliard would sit listening to his playing, finding mistakes. He had all of these psychological impairments that accompanied him, and it wore him out.”

Happy endings

Even though Isacoff had to abandon the book project, he had a lot of contact with Cliburn in the years that followed and kept up with what was going on. “Van was a very generous person. I remember a birthday party for Joseph Bloch — a close friend of mine who taught piano literature at the Juilliard School for fifty years. All the people that went to Juilliard were in his class, including Van. But Van got an F in piano literature, because he never got to class. He couldn’t wake up in the morning. He stayed up all night, and in the morning he would call Bloch’s wife and say: Mrs Bloch, would you please apologize to your husband for me, I just can’t get out of bed. Bloch was in his 90s when he passed away, and I think it was for the occasion of his 90th birthday party, at Steinway Hall in New York, that I got in touch with Van and said: your old teacher who gave you an F is having a birthday party. Van immediately called this florist that he used near Carnegie Hall and had flowers sent over.”

While the tale of Van Cliburn has some of the elements of tragedy, Isacoff points out that there are also a number of happy endings to it. Van Cliburn created a lasting musical legacy and inspired love and admiration in generations of Russians, propelling diplomatic efforts between the rival superpowers. The competition and festival that bears his name is one of the world’s most important piano events, inspiring countless young musicians. On a personal level, the friendships formed in 1958 were lasting: for example, among the people who made a special journey to see him when learning he was ill was Liu Shikun, his Chinese rival at the Tchaikovsky Competition. Finally, what really made Cliburn’s end a happy one was Tommy Smith, the pianist’s life partner during his last two decades. Being with Smith, writes Isacoff, Van Cliburn “was no longer haunted by the past.”

The book on Amazon:

Comments

Thank you so much for leting us have this article, it brings us closer to our dear Van Cliburn life. He was so sweet, and kind and generous, it is so wonderful to ve abble to gaveta book by some one who really admired him.

Muy agradecida. El encuentro con Vanya fue un sueño cumplido que nunca olvidaré.

I have watched Van Cliburns filmed performances from his youth and always thought he was an amazing artist. I was saddened to learn that there was so much pain underneath it all and that he never found help for it. It’s great to be a pianist if you love it but you should have to sacrifice your happiness and freedom for it.