Rhapsody in Blue – A Piece of American History at 100!

The centennial celebration of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue has taken place with a bang and noise around the world. The renowned work of American classical music has become synonymous with the jazz age in America over the past century. Piano Street provides a quick overview of the acclaimed composition, including recommended performances and additional resources for reading and listening from global media outlets and radio.

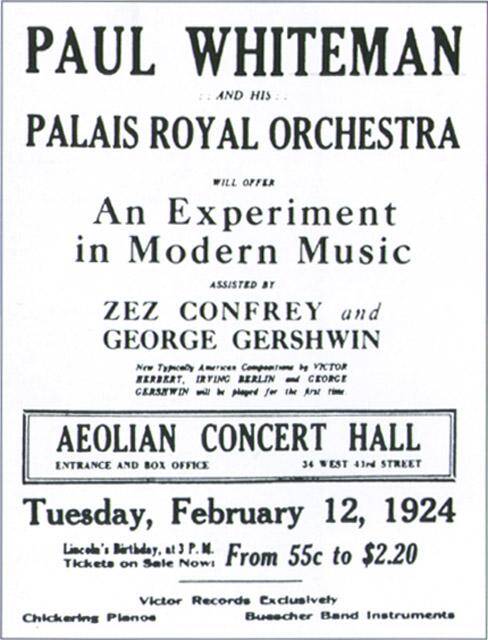

On February 12, 1924, a large crowd gathered at Aeolian Hall on West 43rd Street, which included distinguished figures such as Sergei Rachmaninoff, violin virtuoso Fritz Kreisler, and esteemed conductor Leopold Stokowski as well as many prominent critics from New York. The event was a concert titled “An Experiment in Modern Music,” featuring “Paul Whiteman and his Palais Royal Orchestra” performing a new composition by George Gershwin. Program annotator Hugh C. Ernst, Paul Whiteman’s business manager, described the experiment as “purely educational,” with Whiteman aiming to showcase the advancements made in popular music over the past decade. The goal was to integrate American vernacular music into the concert hall.

It was met with enthusiastic applause, breaking musical boundaries and rules along the way. Despite its success, some critics were not impressed.

It was met with enthusiastic applause, breaking musical boundaries and rules along the way. Despite its success, some critics were not impressed.

Lawrence Gilman, a music critic for the New York Tribune, criticized the piece for its triteness, feebleness, and sentimentality. Another critic went as far as attributing Gershwin’s perceived shortcomings to his heritage as a Russian Jewish immigrant.

Background

Gershwin had established himself as a successful pianist and Broadway composer in New York. His focus on creating music for smaller ensembles and catchy tunes had garnered him a following among theater audiences.

In 1923, Paul Whiteman, a bandleader, mentioned to George Gershwin his idea of putting together a concert of modern music with jazz elements. He asked if George would be interested in composing and performing a jazz piano concerto for the concert. George agreed, but with a busy schedule, he forgot about the concerto until early 1924. He saw a newspaper announcement that Whiteman had scheduled a concert for the following month, where Gershwin would premiere his new piece.

With no notes written and his busy schedule he was under pressure and despite his efforts to expand his orchestration skills, taking on a major orchestral piece for the concert hall seemed too daunting for the 25-year-old. George worked intensely with Whiteman’s arranger, Ferde Grofé, to finish Rhapsody in Blue in time for the concert.

With no notes written and his busy schedule he was under pressure and despite his efforts to expand his orchestration skills, taking on a major orchestral piece for the concert hall seemed too daunting for the 25-year-old. George worked intensely with Whiteman’s arranger, Ferde Grofé, to finish Rhapsody in Blue in time for the concert.

George Gershwin’s brother Ira was consistently by George’s side, offering support, feedback, and occasionally collaborating on George’s iconic tunes. In 1924, while he didn’t have a direct hand in the musical creation of “Rhapsody,” he did propose two key elements that greatly enhanced the success of the new piece.

George played some sections of his unfinished opus for Ira and Ferde Grofé, the composer and arranger who was there to orchestrate the work for Paul Whiteman’s band. After finishing what he had composed so far, George asked Ira for his thoughts.

Ira praised the work but felt that there were too many jazz themes and suggested adding a slower section to break up the rhythmic material. He also recommended incorporating a lush, romantic melody composed two years earlier. Remembering the tune, Ira hummed it for George who initially dismissed it as “corny.” However, as he played the melody on the piano, the rich harmonies came back to him, and he was surprised by its potential.

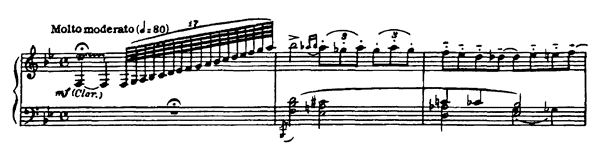

Gershwin began crafting Rhapsody in earnest on January 7, noting the date at the top of his manuscript. He created it as a composition for two pianos, with one handling the solo part and the other providing accompaniment. Grofé arranged the piece for Whiteman’s orchestra, a decision that would prove crucial to the eventual success of Rhapsody in Blue. Handing over the orchestration duties to Grofé not only relieved Gershwin of some pressure but also capitalized on Grofé’s intimate knowledge of the capabilities and limitations of the individual musicians in Whiteman’s group, allowing him to showcase their talents effectively.

Following the jazz band version debut in 1924, two additional versions; concert band orchestra 1926 and symphony orchestra 1942, were created. The 1942 adaptation is now the most commonly performed.

Performances

George Gershwin (1924) – Original “jazz band” version

Kirill Gerstein (2012) – Original “jazz band” version

Leonard Bernstein (1976):

Yuja Wang (2016):

Digital Piano Sheet music

Rhapsody in Blue – Two piano version

Rhapsody in Blue – Solo piano version

Read and listen more:

New York Times penned a controversial opinion piece titled “The Worst Masterpiece: ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ at 100,” where the writer refers to the classical crossover hit as “corny and caucasian.”

A Radio WQXR Special, “Strike Up the Band! A Century of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue” guides listeners on a journey celebrating the 100th anniversary of Rhapsody in Blue with special guests who share insights into the creation and debut of this iconic piece, as well as the evolution of performances and reinterpretations by artists throughout the past century.

Vanity Fair: Rhapsody in Blue reimagined. Olivia Giovetti unexpectedly became immersed in Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” while working on a documentary called “American Rhapsody” for BBC Radio 3. Hear versions in different genres inspired by the work.

Los Angeles Times describes a Big Bang experience with the Rhapsody. It had a confident and energetic quality, unlike anything heard in classical music before. Lively and exciting, and learning more about Gershwin and the context in which he created it, the writer’s appreciation for his work only continues to grow.

The Guardian: The debut of Rhapsody in Blue sparked discussions regarding the connections between traditional “high art” and popular culture, addressing issues of racism, cultural diversity, black music, and identity. These ongoing debates remain influential in shaping modern culture.

Van Magazine: Leonard Bernstein believes that the essence of the “American feeling” should be derived from jazz, rather than solely relying on the blues and 19th century dance music. He delves into intricate musicological analysis of the scales and syncopations of African-American music, and discusses how these elements were incorporated by composers such as Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, Roger Sessions, Charles Ives, and more during his time.

Library of Congress: In Gershwin’s original manuscript for “Rhapsody in Blue,” he included the notation for his piano solo but left a portion blank in the revised version, as copyists were assisting in notating the changes he made during the composition process. This empty section remained in the final score arranged by Ferde Grofé, with a note advising conductor Paul Whiteman to “wait for nod” when Gershwin began his solo.

Comments