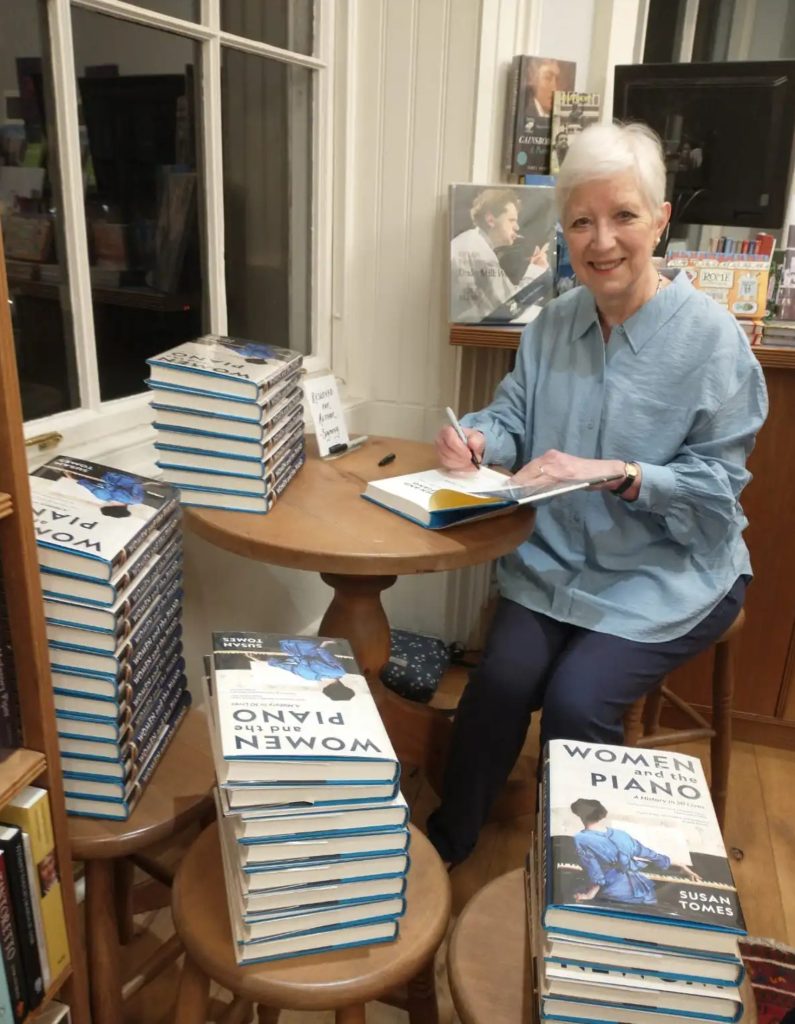

New Book: Women and the Piano by Susan Tomes

Susan Tomes’ latest book is a captivating and thought-provoking exploration of women pianists’ history, praised for its engaging storytelling, thorough research, and insightful analysis. The book combines historical narrative with Tomes’ personal insights as a performing female pianist.

Piano Street: Dear Susan, we were so happy to talk with you after the release of your book “The Piano – A History in 100 Pieces” back in 2021, and just recently your latest oeuvre was published; ”Women and the Piano”. This is your seventh book and this makes us wonder why writing about music is so important for you?

Piano Street: Dear Susan, we were so happy to talk with you after the release of your book “The Piano – A History in 100 Pieces” back in 2021, and just recently your latest oeuvre was published; ”Women and the Piano”. This is your seventh book and this makes us wonder why writing about music is so important for you?

Susan Tomes: I have always been interested in expressing my thoughts in writing, from my earliest years at school. However, I did not find a way to bring it together with music until I was a young professional musician. By then I had some performing experience and was interested in sharing what I had discovered when rehearsing and preparing for concerts. As a member of the group Domus, I used to introduce pieces to the audience before we performed them, and people often told me afterwards that they found my words and descriptions helpful.

This gave me the idea of writing about music from a performer’s point of view. I have also found it helpful to have an outlet for some of the thoughts that go through my head when learning and performing music. Of course, many of those thoughts go into my playing of the music itself, but not all of them!

PS: Your new book sheds light on the male-dominated narrative of piano history by highlighting 50 pioneering women pianists and composers. What was the extensive research process like to uncover these trailblazers and ensure a more accurate account of piano history?

ST: First I should explain that my book is about the history of women pianists, not composers. In the course of writing about them, I found that some of them had composed music, but their music was not my principal focus. As for the research process, I started by looking through the books on my own bookshelf for references to woman pianists. That was a rather shocking experience because there were very few of them. It was also shocking to realise that although I had studied these books myself as a student, I had not consciously noted the absence of women. Now I can see how male-centric most of those books are, but I did not realise it until I started looking for index entries on women. I soon realised that there was a book to be written about women pianists – probably several books in fact. I did my research in the usual ways – in libraries, on the internet, listening to music, talking to people and asking them to tell me of women I might not know about. For example, it was at a dinner party that a fellow guest told me about their ancestor Louise Dulcken, an interesting 19th century pianist of whom I had never heard.

PS: In the course of your research, we imagine you’ve encountered a vast array of repertoire. Music history has traditionally been written from a perspective that elevates certain titans of style as the reference point and definition of their era. Meanwhile, numerous composers and artists have been working on their own unique paths, often unnoticed and marginalized by the historical record. Which female composers or artists did you find particularly stood out in this sense, carving their own distinct trajectories despite the prevailing narrative?

PS: In the course of your research, we imagine you’ve encountered a vast array of repertoire. Music history has traditionally been written from a perspective that elevates certain titans of style as the reference point and definition of their era. Meanwhile, numerous composers and artists have been working on their own unique paths, often unnoticed and marginalized by the historical record. Which female composers or artists did you find particularly stood out in this sense, carving their own distinct trajectories despite the prevailing narrative?

As mentioned, repertoire was not my main focus when writing the book, but I did look at lots of piano music by female composers, to build up a rounder picture of them and their work. One of the most talented was Fanny Mendelssohn, who was discouraged by her family from public performance or publishing her compositions. She wasn’t ‘carving out a distinct trajectory’ – her style was quite like her brother Felix’s, in fact, but her musical expression is (to my ears) sometimes more emotional and imaginative. I admire her cycle “Das Jahr”, a series of twelve virtuoso piano pieces depicting the months of the year.

PS: In March you played a recital at Wigmore Hall which presented nine women composers. What made you choose these and why?

ST: The Wigmore Hall recital was a sort of double event – a book launch for Women and the Piano, and a concert of music by some of those women. I took nine female composers mentioned in the book and made a lovely programme from their piano music. I took care to choose very good pieces – I didn’t want to give anyone the excuse to say, ‘Well, no wonder these pieces are not much played’. In fact, people were fascinated by the quality of the music and mystified as to why they had not come across it before. It has been very gratifying to introduce people to this music. Some people are familiar with it already, but many are not.

PS: Charlotte Gardner (International Piano) raises the question of gender imbalance in piano competitions – a career stepping stone for pianists. While sexism may be a factor, she senses it’s more complex. She wonders if conservatoires hold the key to understanding. The Leeds competition’s decision to address the issue is a positive step in shedding light on the problem. Which are your ideas on how to create a gender equal future for the music scene?

ST: I don’t think I know the answer to that question. Not just in music, but in many professional fields, we still hear regular reports of women being sidelined and under-valued. Things have certainly changed for the better, and there are many positive initiatives such as ‘blind auditions’ for piano competitions. However, there comes a point where the jury (and the audience) wants to see the real person in action. As Charlotte Gardner pointed out in International Piano in March 2024, ‘humans are hard-wired to form an initial response to someone based on visual cues’ – there’s no getting away from that. Even if the entire competition were judged ‘blind’, the winners still have to step out onto concert platforms around the world and be judged for how they look and move as well as how they play. Nobody has yet sustained a career entirely on sound recordings.

There’s a section on competitions in my book on women pianists. I found the same as International Piano did – that competitions are generally won by men. The reasons must be complex. Maybe men are more comfortable in a competitive atmosphere. Perhaps women are not going in for competitions because they feel competitions are ‘not a level playing-field’. Perhaps juries have unconscious bias. Perhaps the repertoire is designed more for men than for women – after all, most composers were male, and presumably wrote for their own man-size hands.

Traditionally, competitions have encouraged pianists to play Beethoven, Brahms, Liszt, Rachmaninov etc in a ‘heroic’ way, because such performances tend to win prizes. In this climate, women are in a difficult position. They can try to play in a ‘masculine’ way, which may go against their instinct, or they can ignore the traditional way, which may displease the jury. But it is not a simple matter of replacing ‘masculine’ repertoire with ‘feminine’ repertoire. Because many historical women were not given training in composition and did not have the time to compose or the opportunity to get their work published, the repertoire by female composers can never quite be the equivalent of the male one. Yes, there are beautiful piano pieces by female composers and these could be put on the menu, but it does not solve the problem of the predominance of ‘manly’ repertoire and our expectations of how it should be performed. There are still obstacles facing women who want to be concert pianists. When the nineteenth-century women in my book were trying to make their way in music, society disapproved of women who thought they could leave their homes, husbands and families to do something as ‘selfish’ as performing on a concert stage. Male pianists were not subject to the same expectations – nobody accused them of being selfish if their children were being looked after by someone else while they played a concert!

Today, the world is full of amazing female pianists, and we can rejoice that some of the most distinguished concert pianists are women. However, quite a few of those high-profile female pianists don’t have children. This may be a positive choice, but it may also indicate the difficulties facing women who want to be concert pianists. Men don’t have to sacrifice a family life to have a career – and nor should women. But for that to become a reality, society would have to change at a fundamental level.

Women and the Piano by Susan Tomes

Yale University Press, 2024

Preview and buy at yalebooks.co.uk

Related posts:

The Piano – A History in 100 Pieces

Comments

A huge problem for women at the piano is the size of the keyboard, which has grown larger over the years and is designed for men’s hands. Pianists for Alternately- Sized Keyboards (PASK) has been at the forefront of promoting different sized keys for smaller hands. I had installed in my piano a 5.5 keyboard, meaning that an octave stretch is 5.5 inches rather than 6.5 inches which is today’s standard. It was revolutionary. Different sized keyboards must become available to women if they are to compete on a level playing field.

This is very important. Thanks for posting this review. I will definitely read the book. By grandmother in pre-WWII Poland was a concert pianist, Romana Mandelbraud. She gave up her career when she got married. She was murdered by the Nazis at Treblinka. And I didn’t realize about the keyboard size as an issue. Thanks for your comment.

One other thought on the interview above. Could it be that competition juries are still male dominated and this may be a factor in women pianists being able to advance their careers? Would more diversity be helpful?