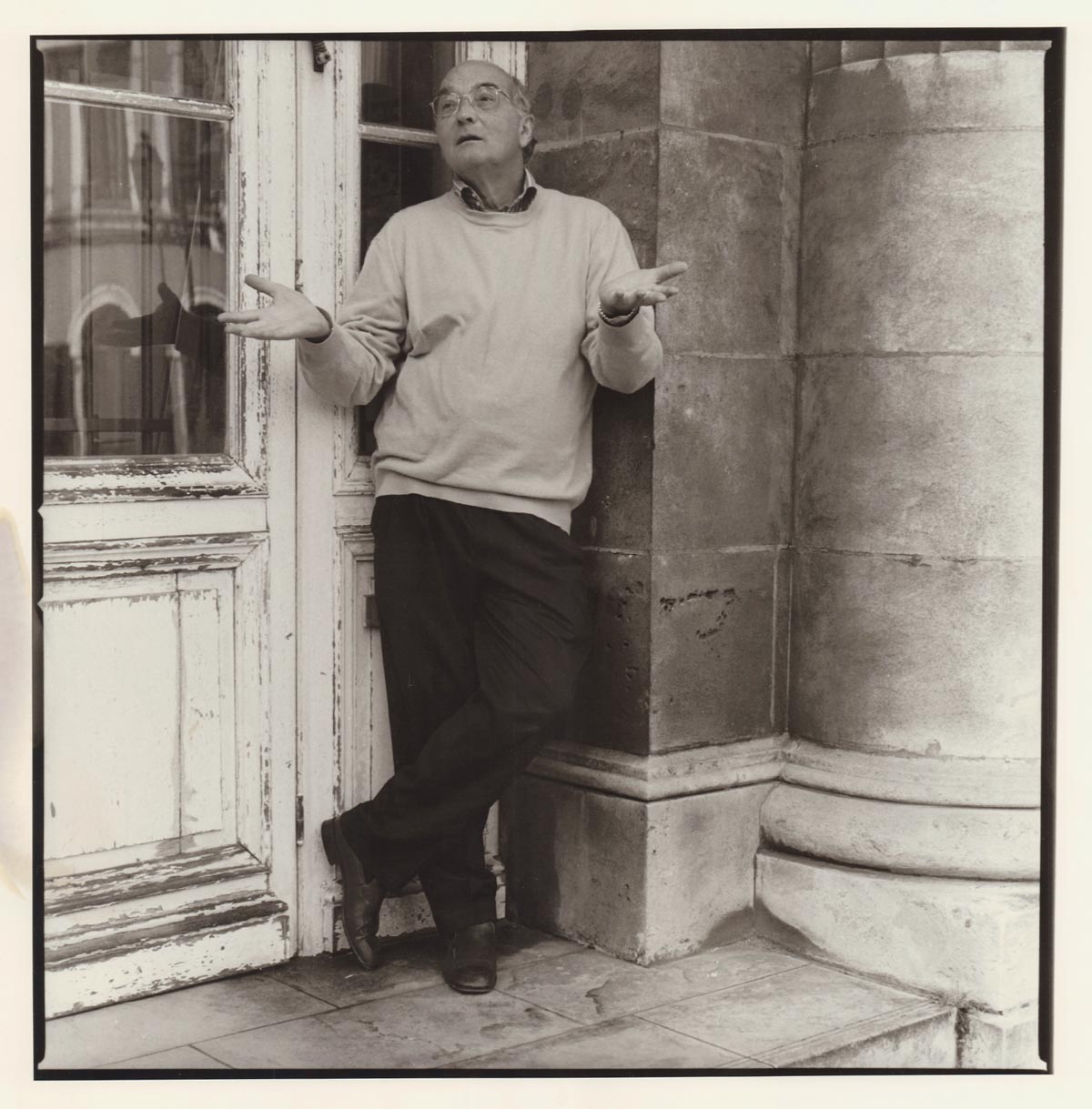

Bruno Monsaingeon – Fascination and Confidence

After his films about greats like Glenn Gould, Yehudi Menuhin, Sviatoslav Richter and many others, films in which he exposes the soul of those artists with great empathy, Bruno Monsaingeon himself is quasi a legend. In recent months, he has been putting the finishing touches to a film about Klaus Mäkelä, the new chief conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. Eric Schoones from the German/Dutch magazine PIANIST had a conversation with him.

Asked about his memories of Yehudi Menuhin, Monsaingeon burns loose in a eulogy that seems to have no end. “When we start talking about Menuhin I can’t stop. He was the great inspiration in my life, as a human being and a musician par excellence, in his youth the greatest virtuoso, purely interested in musical expression. I still miss him every day and half an hour with him was enough for three months of happiness.”

Their first encounter was indicative of Menuhin’s character. The young Monsaingeon was allowed to participate in a masterclass, and after a long day of lessons he asked Menuhin if he could see his score of the Bach sonatas and partitas, curious as he was about fingerings and bowings. Menuhin, who did not always travel with his complete library, immediately bought the sheet music at the local music shop and worked the whole night marking the score with his fingerings and bowings to surprise the young Monsaingeon the next morning. “This story has stayed with me all my life. Can you imagine such a thing? I was a simple student and he was so thoughtful!”

Later, Monsaingeon received many testimonials from musicians who had been helped in their careers by Menuhin, away from the spotlights. “When, as the years climbed, his technique left something to be desired, public perception emphasised his humanitarian work a.o. for UNESCO, while it can all be heard in his music making…”

Monsaingeon also recalls the rare dedication of Menuhin, who did not cancel concerts even when his father died and how, at their very last meeting, he trembled with emotion with the score of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis in his hands. “After many decades, he was still uninhibited and defenceless in the face of music.”

Bruno Monsaingeon and Yehudi Menuhin

Past, present and future

Unlike Menuhin – at the time a household name but now practically forgotten among young people – Glenn Gould, is still very much at the centre of attention. “Every ten years, I see a new generation falling under Glenn’s spell. I think initially he was not understood. His performance evoked a lot of resistance; he was taken for a fool as a provocateur. People had no awareness of his genius and the revolution he brought about in interpretation. His complete withdrawal from concerts only added to the impact of his work. Glenn always makes you feel that he is speaking directly to you. Completely unique, he speaks of past, present and future, there is something about him that is enduring.”

Monsaingeon’s first encounter with Gould was as special as that with Menuhin. To a letter from Monsaingeon written in November 1971, came only after months a reply, albeit 26 pages long, in which Gould went into great detail about Monsaingeon’s ideas and wrote not only about what was on his mind at the time, the recordings of Bach’s French Suites and his Wagner-arrangements, but also about very personal matters such as why he rarely left his home anymore. He warmly invited Monsaingeon to come and talk; it was the beginning of a friendship that lasted for years and which Monsaingeon documented impressively in a number of films and books.

Glenn Gould and Bruno Monsaingeon

Also striking are Monsaingeon’s comments on Gould’s charitable character. “He really hated it when people judged colleagues negatively,” he said. Asked about his thoughts on Brendel, Argerich and Weissenberg, he said only that they were great in Mozart’s piano concertos, Liszt’s sonata and Rachmaninoff’s third piano concerto respectively, while he himself hated those works and would never play them. His aversion to any kind of competition was also a major reason for his permanent withdrawal from the concert stage.”

Mastery

Monsaingeon’s films always stem from a fascination, always resulting in a deep personal contact, in complete mutual trust. Monsaingeon was only interested in artists where, in their mastery, intentions had completely faded into the background after years of study and were no longer palpable in their obvious musicianship. “I don’t make reportage, then reality becomes too concrete, I am looking for underlying ideas and thoughts. Everything in my films is specially conceived and staged for the film, like the recording sessions with Glenn Gould in the 1974 film The Alchemist.” No voice-overs in his films, “a lazy way of making films”. “You don’t need to tell what’s there to see, let the viewer discover that for themselves. I want viewers, not necessarily music lovers, to be able to question the film themselves.”

Clearly, the Hollywood-style productions of late about Bernstein and Celibidache, are not Monsaingeon’s cup of tea.

Photo: Paul Bongartz

Listen

His latest film about Klaus Mäkelä tells the story of three orchestras, from Oslo, Paris and Amsterdam that the young maestro now works with. “It would be terrible to start such a film as a television programme, like: “Klaus Mäkelä is probably the greatest conductor of the 21st century”. Remains that Klaus had a huge impact on me, immediately, from the first minute I heard him, when I did not know his name. This is something much deeper than any superficial media communication, he changed my life just like all the musicians I have made films about, they forced me to translate my own emotions into universal ideas that a wider audience can identify with.” Most recently, Yuja Wang said of her partner in an interview in Preludium: “Klaus exudes trust and respect and gives the orchestra members space. That has everything to do with humanity, you all have the same goal, one is no better than the other. As a musician, you also have to feel free to express yourself. I have discovered that he is of the school of “help, don’t disturb”.”

Monsaingeon: “That is absolutely true. Klaus has the ability to listen and he gives the musicians the illusion of freedom, because he does control everything. For me, Klaus is the synthesis of two favourite conductors of mine: Carlos Kleiber and Guennady Roshdestvensky. With the latter, everyone felt free to play and with Kleiber it was a bit different, you had to be part of the system, but that in itself was so irresistible. With Klaus it’s the same everywhere he goes, musicians can get tired of a conductor, but that won’t happen with him. He masters a huge repertoire and has a fabulous memory. Everything he does is so convincing and I have heard a lot of concerts by now. My film is not about his unbelievable career, I avoid anything sensational. I want him to talk about that quality, everywhere he conjures up that golden sound in a split second. When I said that to him, not as a compliment, but to know how he does it, he just thanked me with a modest smile.”

This article is a contribution from the German and Dutch magazine Pianist through Piano Street’s International Media Exchange Initiative and the Cremona Media Lounge.

Pianist Magazine is published in seven countries, in two different editions: in German (for Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxemburg and Liechtenstein) and in Dutch (for Holland and Belgium).

Pianist Magazine is published in seven countries, in two different editions: in German (for Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxemburg and Liechtenstein) and in Dutch (for Holland and Belgium).

The magazine is for the amateur and professional alike, and offers a wide range of topics connected to the piano, with interviews, articles on piano manufacturers, music, technique, competitions, sheetmusic, cd’s, books, news on festivals, competitions, etc.

For a preview please check: pianist-magazin.de or www.pianistmagazine.nl

Related articles:

Grigori Sokolov Live at Théâtre des Champs-Élysées

Comments