A Massive Glimpse Into Ligeti’s Pianistic Universe

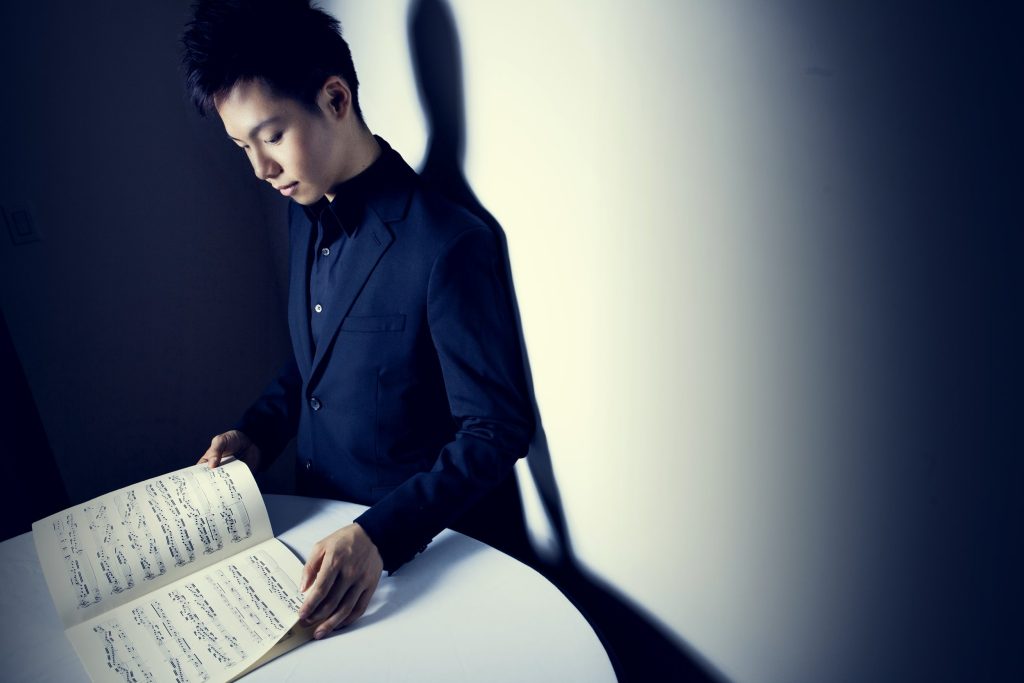

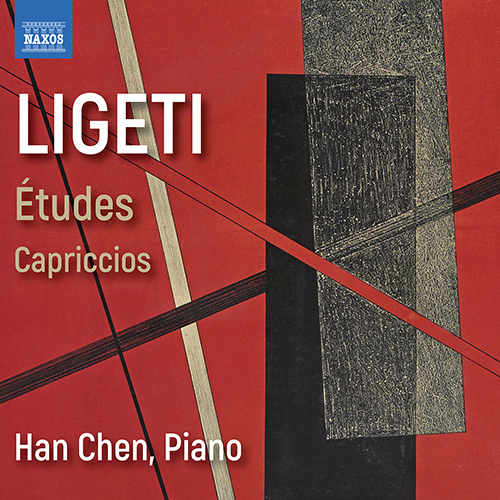

Performing Ligeti’s complete Etudes is a challenge for any pianist. Young pianist Han Chen has received both attention and glowing reviews for his recording of the entire set for Naxos. We had the opportunity to speak with the pianist after his impressive recital at the Piano Experience in Cremona last fall.

Sometimes, sensations occur within the classical piano world that manage to make their way into the mainstream news flow. Whether it’s a sensational piano competition winner or a pianist performing all of Rachmaninoff’s piano concertos in a single concert, it is uplifting to see how piano culture can make a splash beyond the ordinary.

The young New York based pianist Han Chen has made an impression over the past year through his recording of Ligeti’s etudes (Naxos) and his performances of the same works. Praises in Gramophone and New York Classical Review make it natural to want to ask Han Chen some questions about his work with Ligeti’s etudes, which arguably also was a tribute to the composer’s centenary celebration, which took place in 2023. Han Chen is currently preparing a doctoral thesis on Thomas Adès’s piano pieces at the City University of New York named “Traced Overhead”.

Patrick Jovell: Dear Han, thank you for letting us talk to you. 2023 was “Ligeti 100” with celebrations all over the musical world. Can you tell us how this has effected your work with Ligeti’s cycle of 18 etudes – composed between 1985 and 2001 – and what sparked your interest and work with these?

Han Chen: Dear Patrick, thank you for having me. I am very glad that my work with Ligeti’s cycle of 18 etudes has caught some positive feedback, as I truly enjoyed working on them. Ligeti’s music has always fascinated me – I still remember hearing his Atmosphère for the first time in high school and the goosebumps it gave me. I have since heard performances of his piano works throughout my studies. Slightly before the pandemic, I learned the L’escalier du diable. The convolution and the excitement that comes with performing this work left me a deep mark, and when the pandemic hit, I threw myself into working on the complete cycle of his etudes. In a way, it was the only possibility for me to face the perplexing reality at the time, and the labyrinths Ligeti created lent me a dis/comfortable routine to keep a sane life during the lockdown. I knew Ligeti’s centenary was coming up, so I proposed this project to Naxos. It worked out greatly for both sides, and now I become inseparable from these wonderful gems of late-20th-century piano music.

PJ: Since their creation Ligeti’s etudes have made their way up on the concert stage and not least as a fully accepted choice of etude(s) at piano competitions worldwide. Can you reflect on which qualities we encounter in Ligeti’s oeuvre that has brought them up on the parnasse with greats like Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Scriabin and Debussy.

HC: Like all other composers, Ligeti used the form of an etude to create great music that either excites us or breaks our hearts. Ligeti is a master of using limited materials to come up with mind-blowing results, and an etude is precisely that. Although the technical challenges in his etudes are immense, the musical ideas are lucid and straightforward. Reading about the simple mechanisms in the etudes makes it unbelievable how musical they turn out. For example, Désordre’s rhythm evolves by adding or subtracting eighth notes, Touches bloquées is chromatic scales up and down while blocking some pitches, and Fanfares is the same eight-note scale repeated 208 times… all these self-imposed constraints sound so rigid and limiting. However, Ligeti is at his best with seemingly impossible rules. His restrictive rules provide the basis for both the technical challenges and the musical ideas, while his musical genius turns the rules into music that transcends both the performers and the audience.

PJ: The first book of the Etudes pour piano was composed in 1985, marking an 18-year gap since Ligeti last wrote for the piano, mostly in smaller forms. Despite not being a virtuoso, Ligeti admitted that his own inadequate technique was the main driving force behind the composition. However, influences from other composers can be seen throughout the etudes, such as Liszt’s “Il Sospiro” in No. 2, Chopin’s Op. 10/2 in No. 3, Rachmaninoff’s Op. 39/9 in No. 5, and elements of jazz swing in No. 6 with references to Liszt’s “Campanella” and Rachmaninoff’s Op. 32/12. When working on this set, how much impetus or sonic worlds from the old masters do you bring into your interpretations of these works? After all, we also know you as an excellent Liszt interpreter.

HC: Not to mention that the horn calls in No. 4 “Fanfares” can be traced back to Beethoven’s Les Adieux. Technically, No. 12 “Entrelacs” reminds me of Chopin Op. 25-1, No. 9 “Vertige” of Op. 25-6. In addition to the references you mentioned about No. 6 “Automne à Varsovie,” it largely refers to the sighing gesture related to the Romantic era, or the Lamento Motif for Ligeti.

Of course, Ligeti is not “afraid of” looking back to the tradition, unlike other avant-garde composers. He played chamber music with his students and colleagues on the piano, so he is intimately familiar with the classics. For me, it is not only revealing but also exciting to see the connections to the old masters, and I do believe my interpretation leans towards more traditional way pianistically. After all, I encountered his music around the same time when I encountered most of the music I know today, so Ligeti is, so to speak, an old master to me.

PJ: Book 2 written 1988–94 contains eight etudes, and Book 3, four, calmer in charachter written 1995–2001. How would you describe these sets of etudes compared to Book 1?

HC: According to what we know, a couple of pieces in the Book 2 were written around the same time as the Book 1, so stylistically they are closer together than Book 3. He did intend Book 1 to be played as a set, so the structure of Book 1 is more convincing than Book 2 when played in order. I have played all 18 Etudes in one concert, and I put the books in the following order: Book 3, 1, 2.

For me, Book 2 contains the most variety of characters, so it is impossible to summarize it. However, pianistically Book 2 is indeed more intricate than the other two books, as if Ligeti was trying to push the performer beyond the limit (he was indeed doing that!). I love the story of Pierre Laurent Aimard playing No. 14 “Coloana infinită” in which he misses the last note, which is the highest note on the piano, by hitting the side bar of the keyboard, and Ligeti liked it.

Book 3 is not necessary simpler even if it seems calmer. In fact, Book 3 is exploring something that’s more psychologically complex. The running theme in Book 3 is canons, mostly strict canons. Ligeti uses seemingly simple melodies as the dux, and the imitations of the canons create a mystic harmonic language. If No. 1 in Book 1 is two hands playing totally different things (left hand black keys and right hand white keys), the four Etudes in Book 3 are two hands playing the same things but always a bit off. The very slow and very fast tempi in the Etudes create a fraction in the mind that they are canons of the time more than the notes. As Ligeti writes “the fastest” and then “even faster,” the distance between the two hands gets so close that the mind can no longer tell the difference between hands.

PJ: Your album also includes the two Capriccios, written by Ligeti while being a student. The first is chromatic and modern, very structured and built on small motives. The second Capriccio makes one think Bartók’s Allegro barbaro and consists of irregular rhythms and shifting accents. How would you describe them as a performer and why did you couple them with the etudes?

HC: This is an album of music spanning half a century. We see the connection between early and late Ligeti, which is interestingly similar. He likes to start with a simple idea that runs throughout the entire work, and his personal treatment of the idea turns it into a very personal style. Indeed, the two Capriccios are still very much in the influence of Bartók, but we can already hear how he breaks from the tradition. His quirkiness in these two Capriccios becomes his trademark later on, namely the fantastical development of a simple idea and the structure of the development. I find it an intriguing pairing between the Capriccios and the Etudes, while the latter is more complex yet roots from the same characters.

PJ: You are a creative musician and we see you getting involved in interesting and experimental projects. You are also young but with vast experiences. How do the future plans look for you, projects, aims and expectations?

HC: Thank you for the compliments – I love to do different things. In fact, I am so excited about different projects all the time that I am often told to focus on one thing at a time. At the moment, I have just finished recording the Florence Price Piano Concerto with the Malmö Opera Orchestra and conductor John Jeter. It is a great piece that should have entered the canon long ago but luckily we are rediscovering it. Next, I am going to play two very best works by Boulez, the youthful Sonatine for flute and piano, and the masterful Sur Incises for 3 pianos, 3 harps, and 3 percussions. Boulez is the very first modern composer I fell in love with, and I am still inspired by his music. I also continue to commission new works – I have not mentioned that I commissioned 18 works inspired by the 18 Ligeti Etudes last year – and the next commissions are two solo piano works from Anthony Korf and Lei Liang. More classically, I am playing the 12 Chopin Etudes Op. 25 for the first time in a recital in the end of this season. These are all very exciting projects happening in one season, and I aim for more projects that excite not only me but also my colleagues and audience in the future.

This feature is available for Gold members of pianostreet.com

Play album >>

Comments

Bravo, Han!