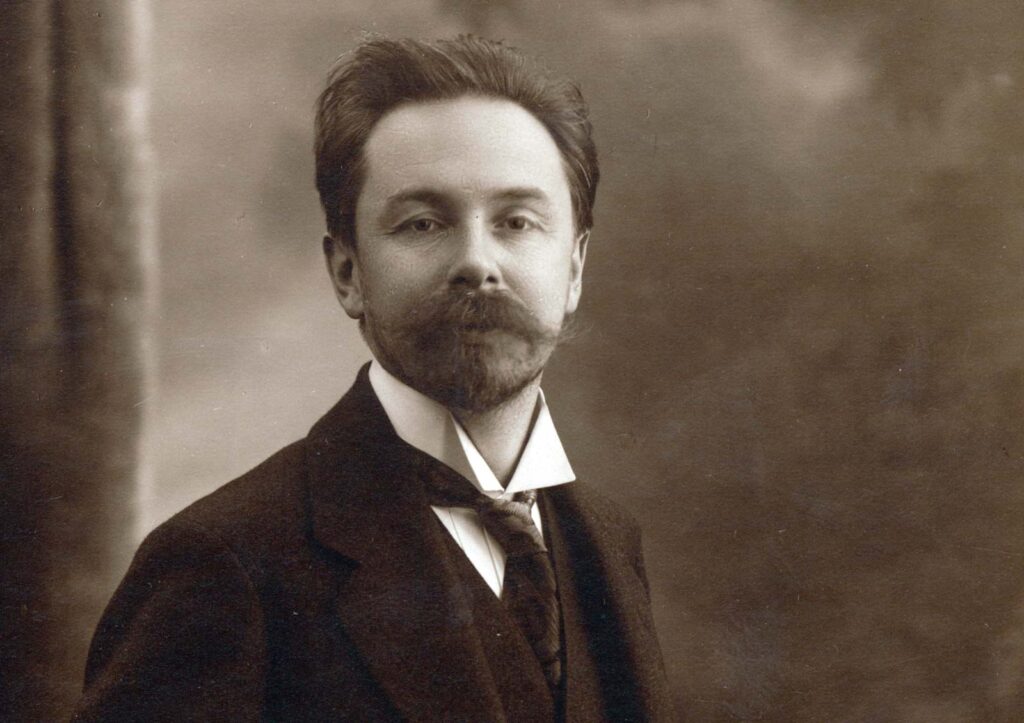

A Genius under the Magnifying Glass – Visiting Alexander Scriabin

Last December, in preparation for the Scriabin 150th anniversary (2022), the new complete edition of Alexander Scriabin’s works was published, in twelve volumes. Eric Schoones spoke to the pianist and musicologist Pavel Shatskiy, who was responsible for publishing the piano works. They talked about the composer and pianist Scriabin, his piano, the influence of Chopin and the A.N. Scriabin Memorial Museum in Moscow.

Pavel Shatskiy is the son of the musicologist Valentina Rubtsova, D.Mus., editor-in-chief of the Muzyka – P. Jurgenson publishing house and deputy research director of the A.N. Scriabin Memorial Museum in Moscow. Her monograph on Scriabin, published in 1989, was one of the most authoritative publications of its time about the composer. Twenty years later she returned to Scriabin’s legacy and led the scientific work on a new edition of his works, which was completed in December 2021. ‘As a small child I heard my mother play Scriabin and I loved both the composer and the performer. No one ever forced me to become a professional musician, but nonetheless I chose the piano, on which you can play very complex chords.’

Pavel Skatskiy studied at the Moscow Conservatory under Yuri Slesarev, himself a student of Victor Merzhanov, from whom the path can be traced back to Samuil Feinberg, Alexander Goldenweiser and Paul Pabst. He is currently the assistant of Prof. Alexander Vershinin and also teaches the practice and history of the performing arts, ‘the subjects that many students try to avoid or forget as soon as possible’.

Chopin

It is often claimed that Scriabin at first borrowed heavily from Chopin’s idiom but, according to Shatskiy, he was not alone. Stylistic allusions to Chopin can also be heard in the works of Arensky, Rachmaninov, Lyadov and many others. Chopin had a significant influence on both the Moscow and St Petersburg branches of the so-called Russian School. His legacy also served as a litmus test to ascertain a pianist’s maturity. ‘Learn to play Chopin – and then you can play anything’, said Anton Rubinstein.

What makes Scriabin unique is his feeling for rhythm and inner pulse, spontaneous mood changes and modulations. ‘To these can be added the intense harmonies. He experimented with chords that included all twelve notes of the chromatic scale. I have always liked his later works best – although even the famous Scriabin performer Vladimir Sofronitsky complained that there was not enough space to breathe in them. For example, I have never tired of listening to the Sixth Sonata – a question of individual attitude and perception. The same applies to Scriabin’s synaesthesia. When giving lectures on this subject, I have heard from many of my listeners that they also perceive some kind of association between music and colour. The problem, however, is that this connection is very individual for each listener. Colours had a sort of philosophical ‘charge’ for Scriabin, some with earthly associations, others with spiritual ones, with light blue (the note F sharp) at the top of the chain. This development is summarized in the ‘Luce’ section of Prometheus.’

Rachmaninov

What is Shatskiy’s impression of Scriabin as a pianist? ‘Perhaps Alexander Nikolayevich did not have the stamina and competitive tenacity of a touring virtuoso like Rachmaninov. After graduating from the Moscow Conservatory, he apparently performed only his own music. Scriabin’s recordings are rare but very valuable, especially those of the miniatures. In his performance of the Étude, Op. 8 No. 12, we hear some wrong notes, but the way he slowly increases the tempo and builds to a climax is absolutely incomparable – no other pianist comes close. His interpretation of the Prélude, Op. 11 No. 1, conjures up the image of waves breaking on the shore; with many other pianists you only hear leaps and groups of five notes. Scriabin’s recordings of his Sonatas Nos 2 and 3 were only rediscovered in the 2000s; they are very interesting, but little attention has so far been paid to them.’

‘Transferring paper piano rolls, made for L. Hupfeld’s Phonola or M. Welte & Söhne’s Welte-Mignon, to today’s sound carriers requires a very special talent and skill – at least, if you want to avoid a strong resemblance to the clunky movements of early cinematography. My favourite versions are by Pavel Lobanov (1923–2016), a sound engineer responsible for restoring archive recordings at the legendary Melodiya label. He graduated from the Moscow Conservatory as a pupil of Vladimir Sofronitsky. The recordings were produced by A.N. Scriabin Memorial Museum.’

It is inviting to make a comparison between Rachmaninov and Scriabin. ‘They were classmates. Rachmaninov was one of the first to give a concert in memory of Scriabin, and he sent all the proceeds to Scriabin’s widow. Both were very egocentric geniuses. Rachmaninov’s artistic views were more conservative, which is probably why he was perceived as more moderate. Unlike Rachmaninov, Scriabin was very interested in philosophy; he was influenced by the theosophist Helena Blavatsky and by Indian spirituality. Sometimes, too, his music is erroneously regarded as offering guidance about or illustrations of philosophical ideas. I am firmly convinced that we should approach it the other way around: the music was the most important, and the philosophy was a source of calm, leisure and inspiration. Despite many sketches, aphorisms and studies of Blavatzky’s Secret Doctrine, Scriabin was not a professional philosopher.’

Rimsky-Korsakov

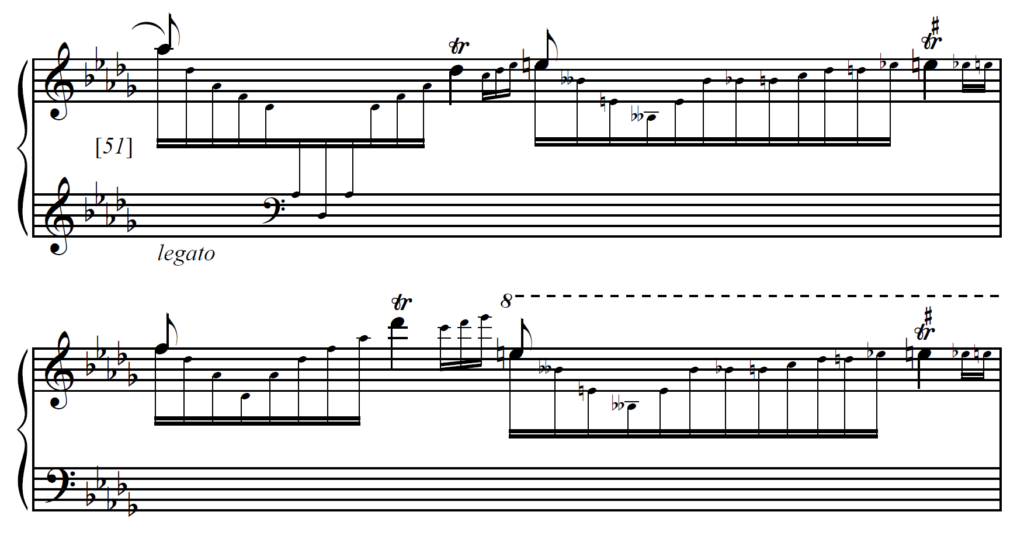

The complete edition is a genuinely pioneering project. ‘For the simple reason that there has never been a complete edition before. We managed to reinstate small but very important details from Scriabin’s manuscripts, and also from first editions and even his own recordings. For example, in the coda passages of the Nocturne for the left hand, Op. 9, most editions lack the sharp sign above the trill (see music example).

Unfortunately, among his earlier works, only the manuscripts of Opp. 8 and 9 and 11–18 have survived. The others, up to and including Op. 51, have been lost, mostly during the Second World War. Scriabin’s manuscripts from his later years resemble calligraphic works of art. We know that he attached great importance to the appearance of his scores: the Poème de l’extase, for example, is impressively beautiful; but things were different in earlier years. In St Petersburg we can find the score of the Piano Concerto, Op. 20, which Scriabin sent to Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, then editor-in-chief of the M.P. Belaiev publishing house. Rimsky-Korsakov tore open the envelope and remarked angrily: “I don’t have time to correct all the wrong notes for this mad genius. We should find someone who can make a good orchestration for him”.’

Bechstein

In addition to his editorial work, Pavel Shatskiy also works at the Scriabin Memorial Museum. This opened in 1922 in the old mansion on Arbat Street in Moscow where Scriabin spent the last three years of his life.

The museum contains original Art Nouveau furniture and its inventory includes more than 7,000 letters, sketchbooks, autographs and a large library of recordings – including Scriabin’s own recordings as well as those by other leading performers.

‘The museum also houses Scriabin’s Bechstein grand piano. On the ivory keyboard we get a sense of the composer’s touch. The instrument is still in original condition and is playable, but great care must be taken. I’m afraid that if we had it restored, the magic would be lost. Because once you’ve heard it, you’ll never forget that sound.’

In 2012 the Scriabin Museum was significantly expanded with a second building, containing a new concert hall with a 3D mapping system, exhibition rooms and other facilities. It has become a gathering place for Scriabin enthusiasts.

Interview by Eric Schoones

This article is a contribution from the German and Dutch magazine Pianist through Piano Street’s International Media Exchange Initiative and the Cremona Media Lounge.

Pianist Magazine is published in seven countries, in two different editions: in German (for Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxemburg and Liechtenstein) and in Dutch (for Holland and Belgium).

Pianist Magazine is published in seven countries, in two different editions: in German (for Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxemburg and Liechtenstein) and in Dutch (for Holland and Belgium).

The magazine is for the amateur and professional alike, and offers a wide range of topics connected to the piano, with interviews, articles on piano manufacturers, music, technique, competitions, sheetmusic, cd’s, books, news on festivals, competitions, etc.

For a preview please check: pianist-magazin.de or www.pianistmagazine.nl

Comments

Brilliant article! Many thanks!