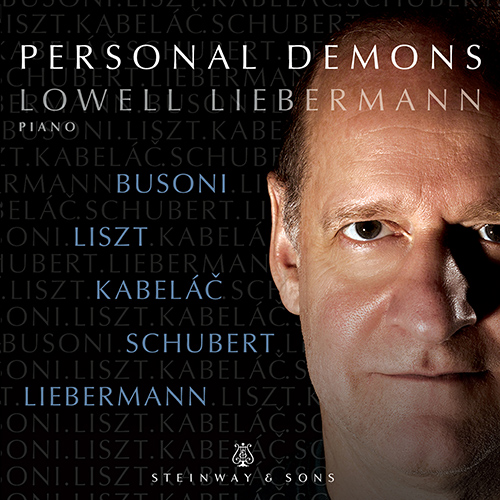

Lowell Liebermann’s Personal Demons

In this exclusive digital encounter with the praised and enigmatic composer Lowell Liebermann on his premiere recording as a solo pianist on the Steinway & Sons label, Piano Street’s Patrick Jovell meets the pianist behind the composer and the composer behind the pianist.

Clearly, Liebermann’s latest album release is in a way an attempt to measure a time span and it’s not only a 60-year celebration but a very personal way to – and by means of the piano – let us follow the composer’s ways into his musical universe. The album contains music “he wish he wrote” and also offers music that he actually has written. Liebermann follows Stravinsky’s dictum; “my music is about the notes themselves and nothing more”, but it still leaves us with the question about the communicating qualities of the composer’s music.

This feature is available for Gold members of pianostreet.com

Play album >>

Personal Demons – album content:

Liebermann: Gargoyles, Op. 29

Kabeláč: 8 Preludes, Op. 30

Liszt: Totentanz, S525/R188

Liebermann: 4 Apparitions, Op. 17

Schubert: 13 Variations on a theme by Anselm Hüttenbrenner in A Minor, D. 576

Busoni: Fantasia contrappuntistica

Liebermann: Nocturne No. 10, Op. 99

Piano Street: Thank you for letting us talk to you about your latest recording “Personal Demons”. Your album contains composers rooted in tradition yet with a strong urge to develop contemporary concepts. They are all solitaires, I wouldn’t say misfits, but persevering despite a lack of understanding in their times. Schubert, one of many working in the total shadow of the great LvB, Busoni, the omni genius without a homeland, Kabelac, rejected by the Czech communist regime and Abbé Liszt, exploring inner, spiritual development and thus new harmonic territories – away from the extravagant superstar showmanship of his early years. In a way the mentioned composers carry personal demons too (Busoni “cannibalizing” on Bach for example) and suggest that this is a way how music can develop through time.

Lowell, you are a pianist and have therefore played vast amounts of music. If you were to extend your list of fascinations – not necessarily demons – which would these be and why?

LL: You are right that the composers on this album are all, in one way or another, outliers, and that is part of their attraction. There are certainly other composers, more mainstream, who have had an even greater influence on my development as a musician. It was Bach who first made me fall in love with music. I was actually first exposed to Bach’s music through “Switched On Bach,” the synthesized versions by Wendy Carlos that have held up remarkably well, I think. But perhaps the most profound influence on my musical growth was Beethoven. My first composition teacher at Juilliard, David Diamond, had me follow a Beethovenian model of keeping sketchbooks and rigorously working out musical materials. And my piano teacher, Jacob Lateiner, was a Beethoven specialist. It was through working on the Beethoven Sonatas with him that I first fully appreciated the interconnectedness of every element of those scores: that the articulations, dynamics, etc, were inseparable from the musical content and development, and not to be altered at a performer’s whimsy. And then there is Ravel, who set a standard of musical perfection that is something to strive for.

Liszt’s Totentanz

PS: Let’s turn to the macabre part on your album and Liszt’s Totentanz, a work he re-wrote as a solo piece from originally being composed for piano with orchestra.

The work is variations on the gregorian chant Dires Irae (the Day of Wrath), a theme used by many a composer. For instance, it appears in Rachmaninoff’s Paganini Rhapsody where it merges with the original theme. You also wrote a Variations on a theme by Paganini for piano and orchestra along with three piano concertos. What do you win or lose when composing for piano with orchestra compared to piano solo?

LL: Of course, when composing with orchestra one gains all the orchestral colors and an enormous amount of creative flexibility that comes with all those added instruments. And I think there is also a special dynamic in the dialogue between a solo piano and orchestra that creates a unique kind of musical tension that also opens up all kinds of possibilities.

PS: What did Liszt gain in the solo version?

LL: Going from the orchestral version of Totentanz to the solo piano version is a very special case, I think. I think the piece gains a certain kind of austerity in the piano solo version that is entirely appropriate and beneficial. At this point, I prefer the solo version. Liszt made a cut in the coda in the solo version which takes some getting used to one is familiar with the orchestral version. Several pianists have reinstated this cut, transcribing those few measures themselves. I can understand the impulse to do so, but I prefer to leave the work it as Liszt saw fit.

Performing own compositions

PS: It’s a joyous favor being able to talk to a composer who is also the performer and history has given us so much amazing music from creators with this combination of function and skill. On the album you give us two of your own works; the immensely popular Gargoyles Op. 29 and your chosen 10th Nocturne Op. 99 (out of eleven, first Nocturne composed in 1987). This poses the question about person vs. persona. When performing your own repertoire, which works do you choose and – to add an even more pathologic dimension – are you interpreting the work or are you performing/projecting yourself?

LL: The composing and performing are two very different functions that require different focus and utilize different parts of one’s brain and psyche. There is a real danger in performing one’s own works that one thinks one knows them better than one in fact does. The kind of learning that you need to do as a performer is much different from the knowledge and memory you have of a piece from having written it. A very high percentage of the memory needed for performance is muscle memory rather than intellectual memory. And so, when learning one of my own pieces for performance, I have to forget that I wrote it, and approach it as if it had been written by someone else. And that includes studying all the dynamic and expressive markings anew, because one can forget one’s own intentions and get sloppy. And this also brings up what I think is a bit of a cliché, that a composer’s music is a direct reflection of their personality, or a reflection their emotional life at the time of writing the piece. This is simply not true. A composer can write a tragic piece at the happiest point in their life and vice versa. It is often more like acting via music rather than writing an autobiography in music.

A desirable pianistic style

PS: You are one of the few contemporary composers who can out the big names and take place in traditional pianist recital programs worldwide. What makes your music so desirable for pianists? Would you mind if I ask for a pianistic self-analysis?

LL: I’ve always felt that it is important for me, as a composer, to keep in contact with the act of performance. It informs my writing in so many ways, even just experiencing the sheer physical joy of playing certain things. I think keeping awareness of the fact that music is an act of communication in real time is very important, and it is easy to lose track of that when one has one’s head buried in the notes. One aspect of my music that, perhaps, has helped its popularity is that, no matter what is going on harmonically, my music is almost always melodically based. My music mixes tonality (usually not in a traditionally functional sense, though), atonality, octatonic or other synthetic scales, etc., basically anything that I feel fits the material at hand. Some critics have called my music neo-romantic (a label I disagree with) and I think what most of them are reacting to is the fact that it is melodically based. It’s just an element of music that I find has to be there to keep my own interest.

Composing for flute

PS: Melodic quality must be a key for any composer but after a look in your works list we very often see works for or/and including the flute. What is your story with this instrument?

LL: My very first commission for flute was a Sonata for Flute and Piano, which was commissioned by the Spoleto Chamber Music Festival for Paula Robison and Jean-Yves Thibaudet back in the late 80s. That piece “took off” in a really big way and started to be played all over the world. One flautist who included it in his repertoire was James Galway, who asked if I would orchestrate it for him so he could perform it with orchestra. I told him I would much rather just write a new Concerto for him, and that led to the commission for my Flute Concerto. Things escalated from there, and there were further commissions from him and other flautists: a Flute and Harp Concerto, a Piccolo Concerto, Flute Trios, etc. The flute community as a whole is one of the most enthusiastic groups of instrumentalists out there, who are constantly on the lookout for new pieces and perform them frequently. They share information and share new pieces. Flute works have indeed become an important part of my catalogue but, contrary to what a lot of people seem to think, I do not play the flute myself.

The post-pandemic period

PS: We wish to congratulate you on your 60th birthday which took place on February 22! In terms of time spans and trajectories and in reference to composers in retrospective, will you now enter a new compositional period?

LL: I think those questions of composer’s “periods” are best left to musicologists after a composer has died, and I’m not intending to do that for a while! What I can say is that, although I don’t know what period I will be entering, I do feel that there will be some sort of tectonic shift in my composition, not so much because of this particular anniversary, but because of the circumstances we have all been living through. At the beginning of the present pandemic, all of my commissions were put on hold, which enabled me to focus on my piano playing and this new recording “Personal Demons”. But this has meant that I have not actually written anything new for the better part of a year, the longest amount of time I have ever spent without finishing a composition. Now that there are flickers of light at the end of the tunnel, the commissions are being rekindled, and I do now have to start writing again. But I think the time away from writing will have a natural effect of reassessment. How that will manifest itself, I can’t really tell until I do start writing again, which should be any day now…

Comments

It’s great to see composer-pianists still exist. Back in Chopin’s and Liszt’s days it was commonplace for a composer to be performing his own work as his main concert activity. Nowadays the landscape has shifted to performers mainly playing works by dead masters. It would be so cool if more pianists followed Liebermann’s example and wrote and performed their own compositions on the stage and in the studio again.

A very interesting and informative article. It is refreshing to hear of a musician who is both a performer and a composer in the 21st century, as this combination is no longer the norm as it was up to the late 19th century.