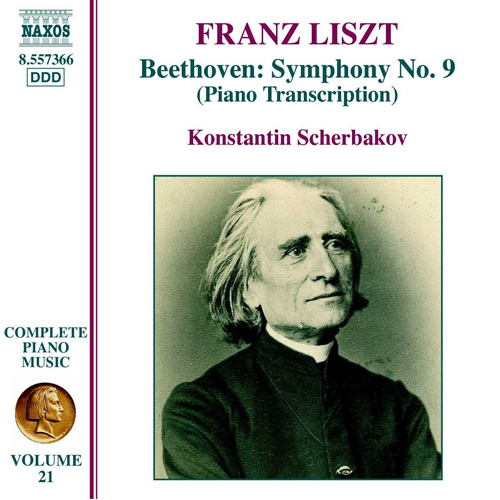

Beethoven as Improviser? – Interview with Konstantin Scherbakov, part 2

In this second part of our interview with Konstantin Scherbakov about his Beethoven celebrations during 2020, we talk about Liszt’s Symphony transcriptions and the improvisational aspect in Beethoven’s music.

Read the first part of the interview here >>

Patrick Jovell: We often picture Beethoven in a large sonata – and in a minor key. However only 9 out of the 32 were in minor and 23 in major…

Konstantin Scherbakov: It is true that Beethoven’s music is often associated with the iconical C-minor key. However Beethoven of, say, F-major is as much of a genius as Beethoven of D minor or A-flat major. There is simply no tonality where Beethoven wouldn’t leave a benchmark in musical history: C major, E major, even otherwise obscure F-sharp minor (slow movement of the “Hammerklavier”-Sonata), F-sharp major (Sonata op. 78) or B major (slow movement of the 5th Concerto). You name it!

PJ: You play all the concertos, sonatas and also Liszt’s symphony transcriptions. Which was your way to build an understanding for the composer over the years?

KS: My understanding of Beethoven’s world grew parallel to my musical consciousness in general and with my ability to play the piano in particular. Initially, the problem of playing chords at the beginning of the slow movement of Op. 7, paired with unattainable meaning, represented an unsolvable problem. The problems I am trying to solve today lie rather in understanding his musical, aesthetical and social goals and, as a result, in the search of the Ultimate Expression. Here the comprehension of Beethoven’s world through his works mirroring his life goes hand in hand with my own life experience. Of course, playing most of his output in cycles, like complete Symphonies or Complete Sonatas, has had an immense influence on the process of understanding and adds to my ever growing astonishment, which I also gained through the experience of getting very closely acquainted with the music of other composers, such as Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, Godowsky, Respighi, Tchaikovsky, Scriabin or Medtner.

PJ: You belong to the few acclaimed pianists who recorded and play the Liszt transcriptions of the symphonies. How do you treat the orchestral/choral material and dimensions in comparison to interpreting his piano compositions? Is there a Scherbakov formula?

KS: This question arises as soon as a pianist approaches the Symphony in transcription for solo piano, and it is perhaps the most important question to answer. How to play a Symphony on piano? It is necessary to stress that Beethoven conceived his piano music as music which could not be played by other instruments. He thought in pianistic terms, he heard this music being played on piano. Likewise, while writing quartets he was thinking and hearing music in quartet terms. The same is of course valid for the symphonies.

So, from the composer’s point of view there is nothing or very little in common between a symphony and a piano sonata. The creative method might be similar but the means chosen are totally different. There have been other transcriptions of Beethoven’s symphonies made by lesser composers and the results were modest. It needed the genius of Liszt to complete the task. Liszt alone made the impossible – to translate the large-scale format into the language of piano: an independent piece came into being where just the means were necessarily reduced. And here is the core problem: it is impossible to imitate the orchestra on a piano. All attempts would fail. Piano will always remain piano. However, one can use the mighty resources of it to emulate the symphonic nature and maintain the spirit of a symphony. So, I made a decision. For me, the transcription of a symphony on a piano should be a PIANO PIECE. In return, after having studied the symphonies one inevitably hears so well-known sonatas in a different, enriched and more detailed way. That’s exactly what lets me have a new look at them at this important nine-months time period when I am playing and recording the complete Sonatas.

This feature is available for Gold members of pianostreet.com

Play album >>

PJ: Tracking down Beethoven always leads us to investigate the improviser. His elaborations on the Fantasia concept and all Variations open up to a discussion on how to interpret the material with an ”in the now” quality, so to speak. Which are your thoughts on the improvisational aspect in Beethoven?

KS: Throughout Beethoven’s entire legacy we see his interest in Improvisation or Variation. However, he used Variation rather as a method of organization of music material. For various reasons this is especially noticeable in his piano works, of which not the least is the fact that Beethoven was one of the most outstanding virtuosos of his time. The ability of playing the instrument implied then first of all the ability of a pianist to improvise. The nature of improvisation which brings together the pianist, his mind and spirit with the instrument in a spontaneous expression was an ideal field for liberation of Beethoven’s titanic talent, fantasy and temperament. However, improvisation itself was for him not the goal but just another means of exploring and understanding the material, its expressive capabilities, its potential in terms of changing and transforming. In this sense, improvisation as a principle of organisation or method of composing pervades a huge amount of his piano works. Beethoven wrote variations throughout his life, and it is quite symbolic that one of the last piano works he wrote was a magnificent cycle of variations (Diabelli).

However, it is necessary to distinguish between variation in Beethoven’s output as a genre layer, and variability as a way of processing the material. In the most general view, Variation can be conditionally divided into a) the way of thinking, b) the way of organizing the material. In the first case, we can talk about the motivic and figurative development of the material, in the second – about the influence of such on structure and form. Generally speaking, all his life Beethoven wrote variations on one favourite theme: the Tonic (I) and the Dominant (V) and their relation. Like no one in the past, Beethoven used the colossal potential of these two harmonies, explored all the musical and formal possibilities that this theme offers, together with the philosophical and aesthetic aspects of such a confrontation. He found his Philosopher’s Stone, which served him throughout his life as a truly inexhaustible source of inspiration, giving him the opportunity to rise to magnificent musical heights which have become since then the property of mankind: the beginning of the 5th Symphony, and the main theme of the 9th Symphony’s Finale being just two most famous examples. One of the most exciting examples of bringing together structure and improvisation, variation and motivic development we find in the 1st movement of the 6th Sonata in F major, Op. 10, where the T-D-T end of exposition unexpectedly becomes the base material for the development section! Figuratively speaking, T-D is the “eternal” Beethoven topic and most of his works are just variations based on that theme.

From this perspective, Beethoven developed variation as a composing method. He even brought this method to work whenever he approached the Sonata form. The illustration of this thesis is best shown in the transformation of the idea of a sonata form which underwent an unimaginable change during four decades, from the first sonata to the 32nd, from the first symphony to the 9th. Indeed, you just have to put the Hammerklavier-Sonata – the true symphony – against the most concise but perfect sonata form of the first movement of Op. 101 against each other to find out how much Beethoven varied the sonata formal principles (and how capable he was to do that)! What can be more contrasting in the use of those? Beethoven improvised upon the sonata form! Having said this I would have to conclude that performing Beethoven’s music would inevitably involve improvisation. Instead I would insist that it does not need improvisation as the expressive tool due to the nature of its semantics. Beethoven’s ideas are so clearly defined that they would not tolerate even the slightest uncertainty, whose momentum, due to the nature of the very concept of improvisation, would otherwise violate the rigor and grandeur of his thoughts. This uncertainty will inevitably be expressed in temporary freedom. Playing “in time” perfectly matches the idea of the “absolute” in Beethoven’s music. I am deeply convinced that the problem of time remains decisive in the execution of Beethoven’s ideas, in their proper formulation. The slightest changes in time (or dynamic or articulation) will lead to liberty of reading and, thus, away from Beethoven’s generalizations, from the transpersonal, supremacist nature of his music. Generalization is the central means of expression in Beethoven’s musical aesthetics and philosophy. He rises to his true heights when he reaches a generalization of the absolute level.

Comments

The assertions of this man and other famous classical musicians such as Gould, regarding improvisation, deepen my conviction that they themselves cannot and have not improvised and are utterly clueless about its nature and effect.

I find the first comment here a bit strange. As somebody who improvises himself, the comments on Beethoven’s improvisational activities make sense to me. I would also expect improvisation to be different for different individuals.